Summary

I’ve observed many companies struggle to build a successful ads revenue business. They build reasonable solutions for personalized feed, recommendation and search systems, but they fail to build a successful ads optimization engine. I started this series to share my learnings and hopefully help those who are in the early stages of their ads optimization journey.

Ads Ecosystem

In an advertising ecosystem,

- Publisher: wants higher ads revenue

- Advertiser: wants higher return on investment (ROI)

- User: wants to see more relevant ads (or less irrelevant ads)

Each advertiser can create ads targeting specific users, provide a budget, set a goal, … and the publisher decides which ads to show to which users and as we show an ad to users, we consume the ad’s budget. When an advertiser’s budget is depleted, it’s beneficial for the publisher to cease delivering that ad.

Common Fallacies

Let’s start by outlining some common misbeliefs as people start to build ads optimization. If you are surprised by any of these, stick around as we are about to learn a lot of cool stuff together!

The Best Ad

Often people think they should build a system that finds “the best ad” for every user. This is an incorrect way to think about the problem and often times leads to building a suboptimal solution. Note that a sound ads optimization solution sometimes may even choose to not show any ads to the user.

Solving with ML

Companies hire ML engineers to build models and improve ads just to realize even outperforming random delivery might be a challenging task. The problem is, at the core, allocation is not an ML problem but a constrained optimization problem that needs to be understood and solved properly. After building a proper optimization framework, ML will become an integral part of that system.

Ad Relevance

You might think the goal of ads optimization is to build a system that maximizes relevance across the board by showing the most relevant ads to users and use “clicks” or “CTR (clicks/impressions)” as the success metric. We will see how such formulation would harm revenue and the advertiser value, and it won’t even help the platform or the user experience in the long run.

Budget Pacing

Many believe that you need a budget pacing algorithm that spends the budget of your ad smoothly throughout the day. But we will see why the true objective of a budget pacing algorithm is not really to pace the spend of your ad’s budget but to actually maximize advertiser’s ROI.

Setup

In order to get started, let’s discuss the setup we will be working with. Since ads ecosystems are complex, let’s start by simplifying the setup by adding a few constraints. Once we have a clear understanding of the simplified setup, we can start removing these constraints one by one to bring our solution back to the realistic world.

Auction

Typically, how an adserver works is it receives an ad request for a particular user. The adserver either returns an ad or it returns no ad. Think of it as if we are trying to sell the user’s attention to a set of eligible ads. So, we run an auction where each ad gets to bid on this user’s attention. The highest bidder wins the auction, and we return that ad. If no ad bids, we don’t have any ads to return. Keep in mind that in reality advertiser gives us some information, and we compute their realtime bid on their behalf in the auction. We also typically don’t want to sell our impressions below certain price, this limit is commonly referred to as “floor”.

Pricing

We also need to decide how much to charge the bidder (advertiser) for that impression. There are three common pricing strategies:

- fixed: some fixed amount, say 1$.

- first price: price = bid

- second price: price = bid of the runner-up (or floor, if no runner-up)

Let’s pick second price here for simplicity.

Simplifying Assumptions

- There is only one ad in the system

- User traffic is constant

- Every user visits the platform once (impressions = reach)

- We run a second price auction (given only one ad, price = floor)

- We have an ML model that predicts

p(click)for each user (suppose the model is super accurate)

With assumptions above, we can understand optimization much easier. With only one ad in the system, the goal becomes maximizing total clicks and relevance (although this doesn’t necessarily hold for more ads, which we will cover later). We will focus on understanding optimization, various pacing methods and their impact on optimization. Furthermore, we will see how the optimal solution looks like and will dive into how to build a system that achieves that optimal solution.

Visualization

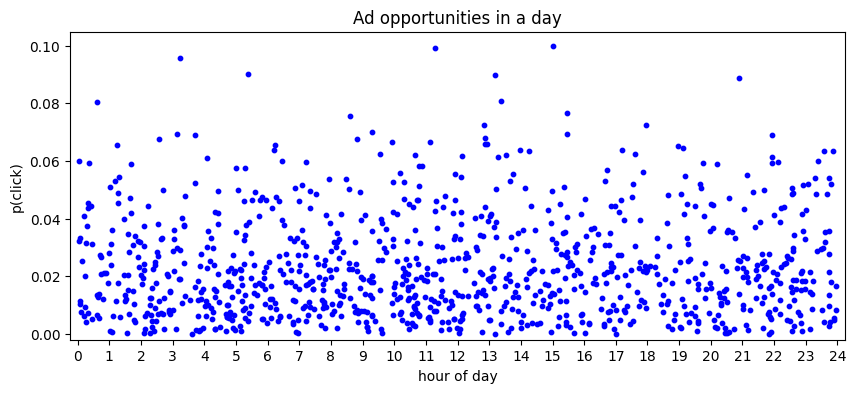

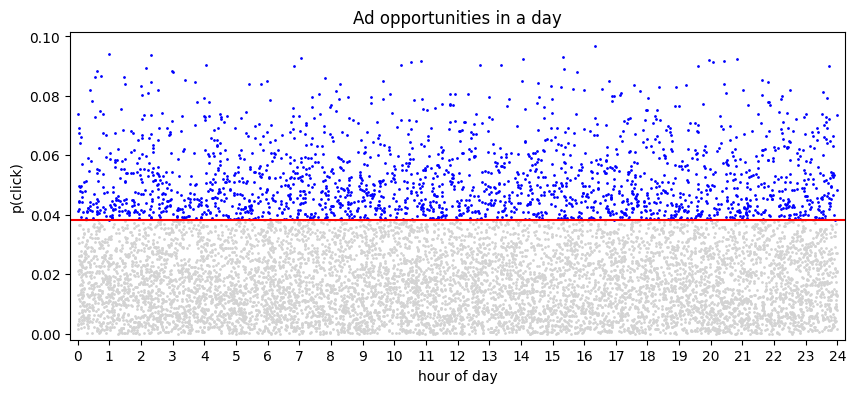

We are going to use this visualization throughout the series.

- The x-axis is time (ex: a day) and the y-axis is

p(click). - Each dot represents an opportunity to show an ad to a user

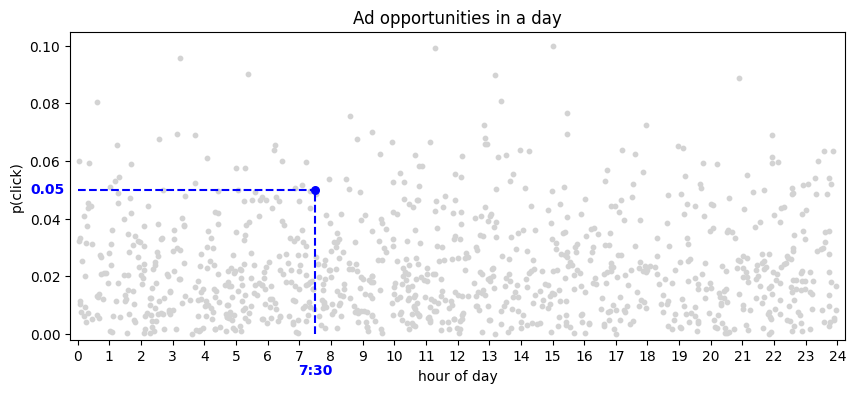

The point in the graph below shows an opportunity to show our 1 ad to a particular user at 7:30am and the model predicts the user is 5% likely to click on the ad.

Pacing and Optimization

Suppose we have the best ML model possible that finds the best ad for every user. Note that if we only have one ad in the system, that one ad is always the best ad for every user. Note that in this case we cannot utilize the power of our ML model at all. We want to build a system that works in any situation and with any number of ads.

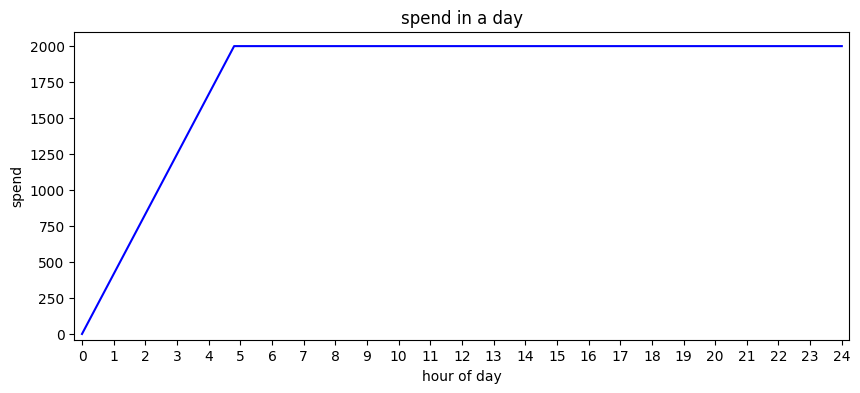

No Pacing

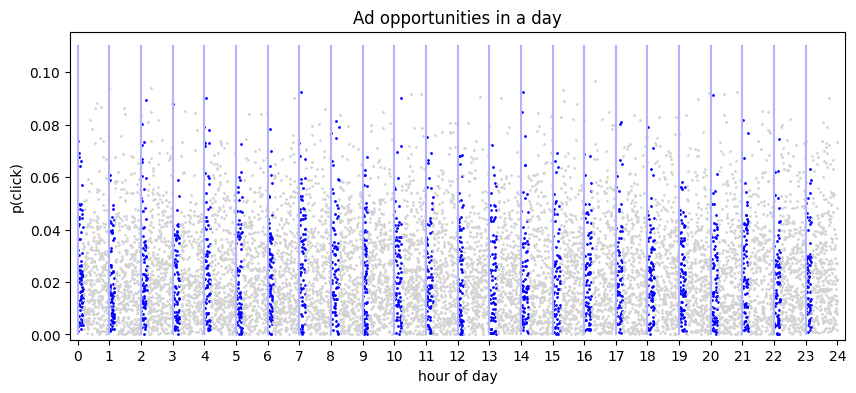

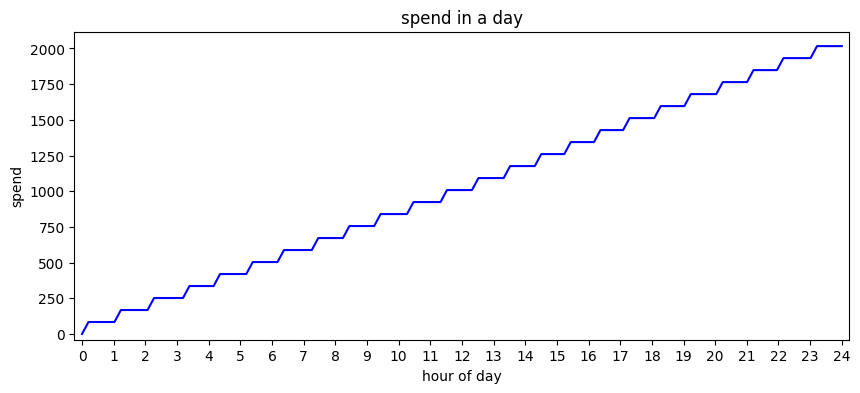

If we run ads delivery with no pacing, we simply deliver this ad to the first N users in the day and won’t deliver for the rest of the day, as shown below both in terms of opportunities captured and spend over time.

Bucketized Pacing

One thought might be to split the budget into 24 buckets and spend each in an hour. We now can spend the budget throughout the day but if we pay attention, what really happened was splitting one big spike into 24 smaller spikes.

Probabilistic Pacing

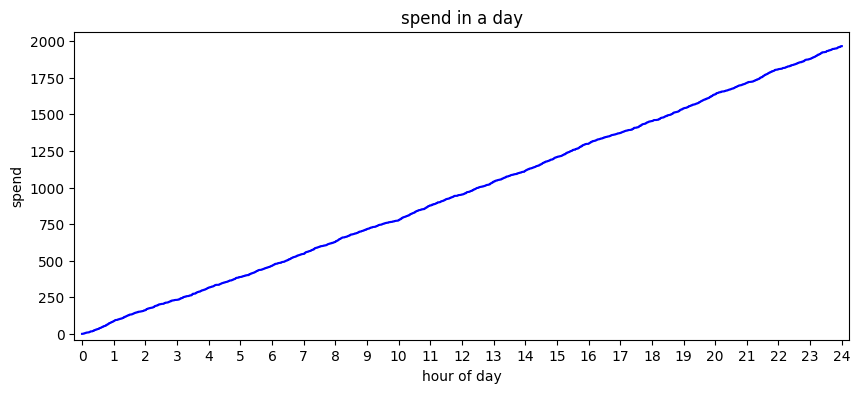

As we try to expand this idea to minutely, secondly, … buckets we realize that we might end up with less than 1 impression in a bucket. For example, we might end up with a bucket with 0.01 impressions, which means we should deliver an impression with probability 0.01. This line of thought leads to probabilistic pacing. We narrow down the buckets to the smallest unit possible, which is “one auction”. For every auction, we compute the probability of inclusion for this ad into the auction and as shown below we can perfectly spend their budget “smoothly” throughout the day

Performance

Evaluation

While it seems like we made some step by step progress, did we really objectively improve anything? We can visually observe that we are still selecting random opportunities throughout the day, despite having the best ML model. We can also sum up the p(click) of the opportunities we selected as a proxy for expected clicks from each delivery:

| Algorithm | Expected Clicks |

|---|---|

| None | 46.6 |

| Bucketized | 47.8 |

| Probabilistic | 45.9 |

You can see that the delivery hasn’t really improved and the variation is simply due to randomness.

The Best Allocation

Given we pay the same price for all these opportunities, we always deliver budget / price impressions independent of opportunities selected. So, in order to maximize total clicks we need to sort opportunities by p(click) and select from the top.

The table below shows how picking the opportunities with the highest p(click) will more than 3X the performance of this ad. Note that this highly depends on the distribution of these predictions as well. Here we are using some randomly generated probabilities with gaussian distribution.

| Algorithm | Expected Clicks |

|---|---|

| None | 46.6 |

| Bucketized | 47.8 |

| Probabilistic | 45.9 |

| Optimal | 140.8 |

The Ads Optimization Engine

Let’s figure out how to build an ads optimization engine properly.

The Optimal Solution

As we covered in the previous section, the optimal allocation is achieved by selecting opportunities from top to bottom (picking the highest p(click) opportunities first).

Given a particular budget for an ad, we need to find the optimal p(click) threshold to spend their budget in full. Let’s call this optimal threshold p*. Note how picking a larger threshold would result in finishing the budget too early and picking a lower value would result in not finishing the budget in full.

Observation 1: "The problem of ads optimization is finding the optimal p* threshold"

Now, if we could use a time machine, we would first observe all opportunities in the day to figure out the value of p*, then we would pull a lever and go back in time, and we would only show this ad to users where p(click) > p*.

If you think about it, instead of picking “the best ad”, we are picking “the best users” for this ad, and sometimes we choose not to show any ad to users in order to deliver the best performance for this ad.

Also, note that picking the top users using a horizontal line is always the optimal solution independent of traffic patterns.

Finding the Optimal Solution

Since we don’t have access to a time machine, let’s see how we can achieve this in real world.

Auction

Before we get started, let’s slightly change the approach towards the solution for better flexibility and to be able to extend it to more than one ad later on.

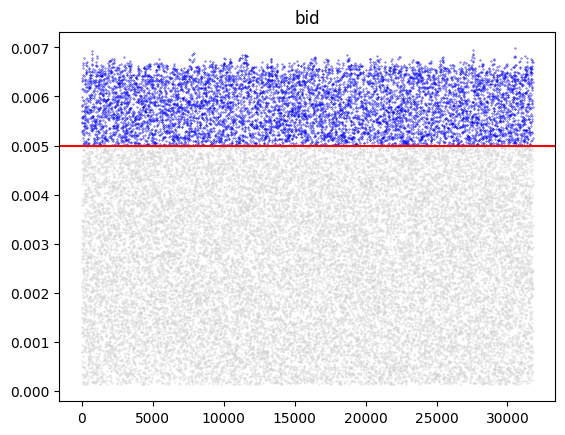

Floor

Floor is a fixed value and bids below the floor are not considered for auction. Ex: floor = 0.02.

Bid

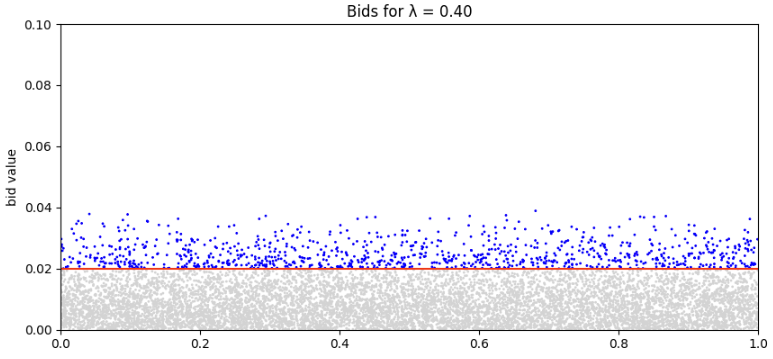

In order to be able to move opportunities above or below the floor, we introduce a variable λ and define our bid as:

bid = λ * p(click)

λ is in [0, 1].

Price

For the sake of this doc, we assume we run a second price auction and in the absence of competition,

we have: price = floor

Auction

We have a simple auction with only 1 participant that wins in auction if and only if bid >= floor.

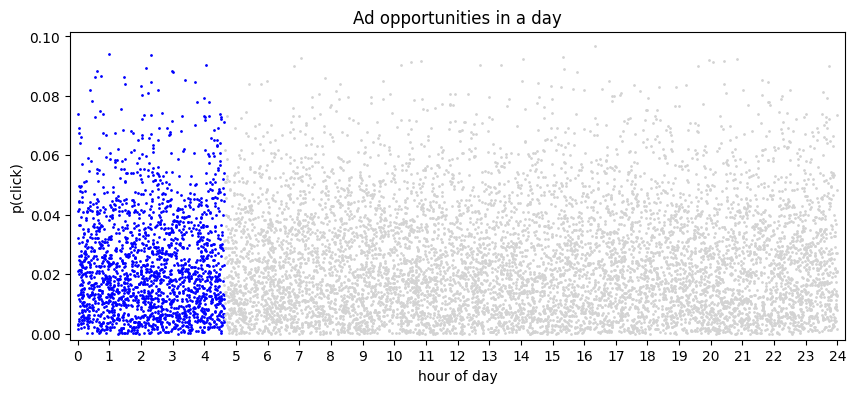

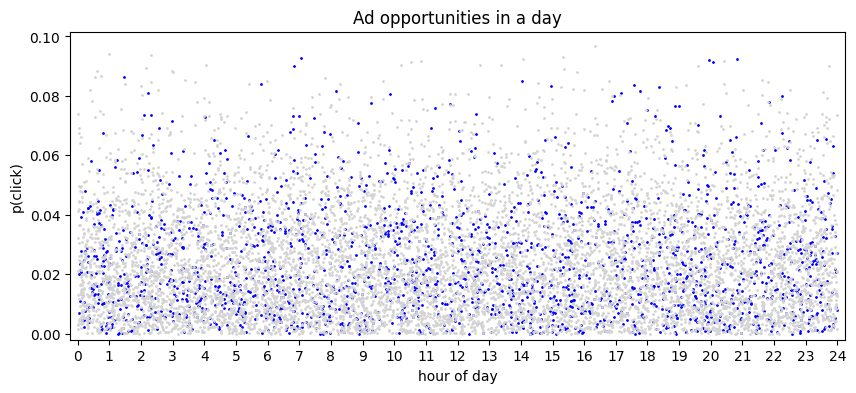

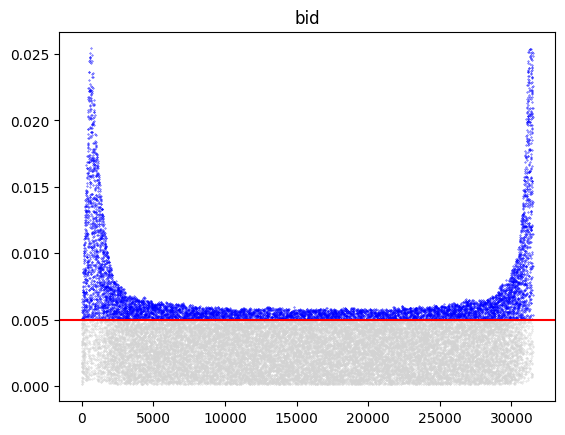

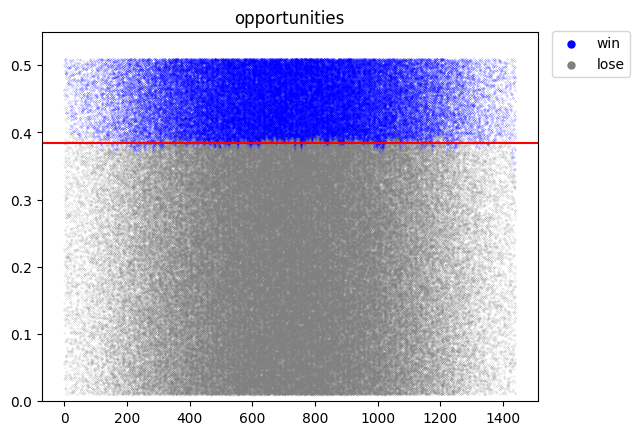

This setup similarly allows us to select top ad opportunities via modifying the value of λ from 0 to 1. The winners of the auction are colored in blue in the graph below.

Pacing

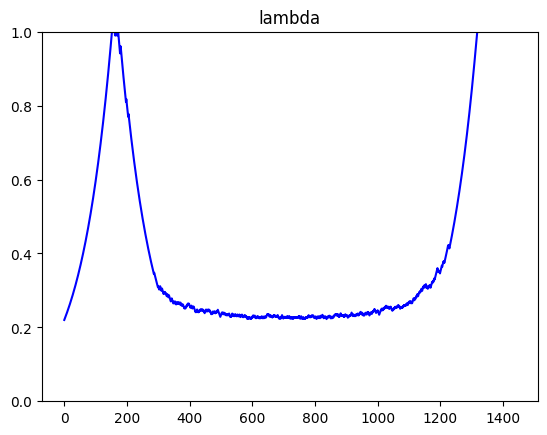

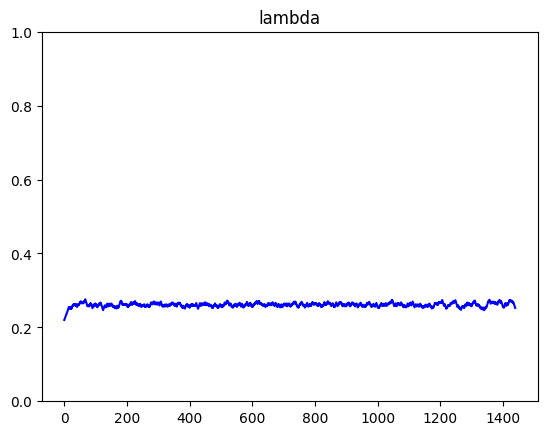

Lambda (λ)

As we observed, λ acts as a bid multiplier and controls delivery by “shading” the bid (hence the term “bid-shading”). Note that a higher value of λ will result in equal or more spend (monotonically non-decreasing).

The Optimal Lambda (\(λ^*\))

Suppose the function S(λ) returns the spend achieved using the bid multiplier λ. For example if we can spend a budget of 100$ using λ = 0.4, we can write S(0.4) = 100.

Note that a value lower than 0.4 would lead to not being able to finish the budget and a value higher than 0.4 would lead to finishing the budget early and missing out on the rest of the opportunities in the day.

Observation 2: "The problem of ads optimization is finding the optimal pacing multiplier λ such that: S(λ) = Budget"

Computing \(λ^*\)

The main challenge of solving budget pacing is to:

- Figure out how much we should have spent in a given time period

- Observe how much we actually spent in that time period

To solve (1) we need to be able to predict future, to some extent, and (2) can be solved via a closed loop control system.

Relaxing Constraints

we initially introduced several constraints to simplify the problem, a common strategy for tackling complex issues. With a clearer understanding of the simplified scenario, we can now begin to relax these constraints incrementally and observe how our solution adapts.

In this section, we will focus on removing two of the previously imposed constraints:

- one ad -> multiple ads

- constant traffic -> variable traffic

By lifting these constraints, we aim to examine how our solution evolves and better aligns with real-world conditions.

Multiple Ads

We simplified our setup by considering only one ad in the system. In a stabilized marketplace with stable eCPMs, treating the competition from other ads as a baseline to compete against is a reasonable approximation for the general case.

However, our original formulation, where we set the bid as bid = λ * p(click) was designed to maximize clicks and relevance. This formulation makes sense for one ad but if we apply it to an ad marketplace with more than one ad, we would build a platform that attempts to maximize total clicks in the system (i.e. CTR, assuming impressions are constant). This formulation has many problems, including but not limited to:

- It’s harmful to revenue (we’re not maximizing revenue or advertiser value)

- It’s harmful to the platform (we prioritize cheaper/clicky ads)

- It’s not extendable to optimization goals other than clicks (purchases, installs, views, etc.)

Recognizing that solely maximizing total clicks (or CTR) may not be optimal, we should instead prioritize a more desired objective. While specifics vary, a prevalent strategy involves maximizing “total advertiser value” known as AV.

Assuming each advertiser indicates they derive a value of V from each conversion (e.g., click), the perceived value for each impression is V if a conversion occurs or 0 if it does not. Since we lack information about future outcomes during the auction, we adjust our objective to maximizing the “total expected advertiser value” known as E(AV). E(AV) (or EAV) is defined as: \[E(AV) = V * p(click)\]

Now, to maximize opportunities with the highest expected advertiser value (EAV), we use bid shading to determine the bid, similar to our previous approach with click maximization. \[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} bid & = \lambda * E(AV) \\ bid & = \lambda * V * p(click) \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]

We often refer to V as the max_bid given we typically shade that bid to a lower value using λ. Developing an incentive-compatible optimization framework ensures these values are aligned with advertisers’ overall valuation of conversions, which involves applying principles from auction theory and pricing strategies.

In conclusion, our final bid is calculated as follows: \[bid = \lambda * max\_bid * p(click)\]

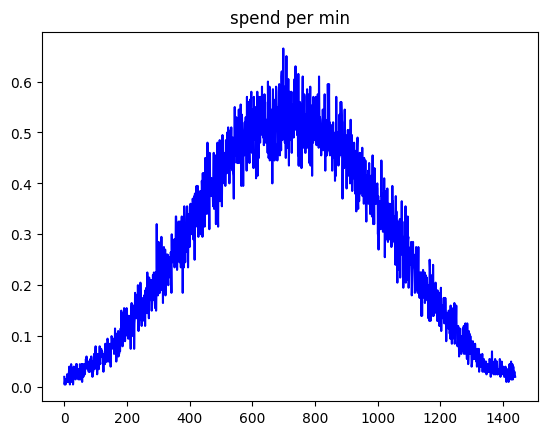

Variable Traffic

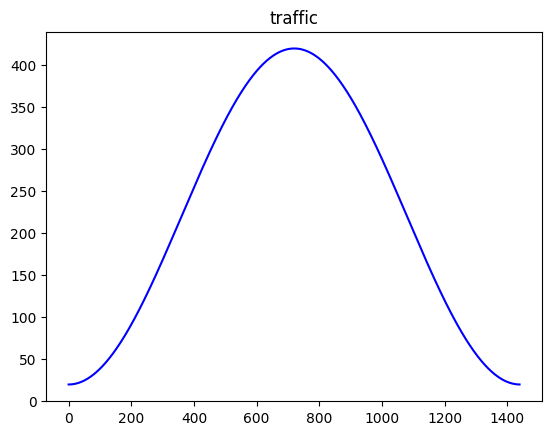

Previously, we operated under the assumption of constant traffic. Now, let’s explore strategies to accommodate diverse traffic patterns and assess their impact on overall advertiser ROI. Suppose the user traffic varies as depicted below (traffic = number of ad opportunities at every point in time):

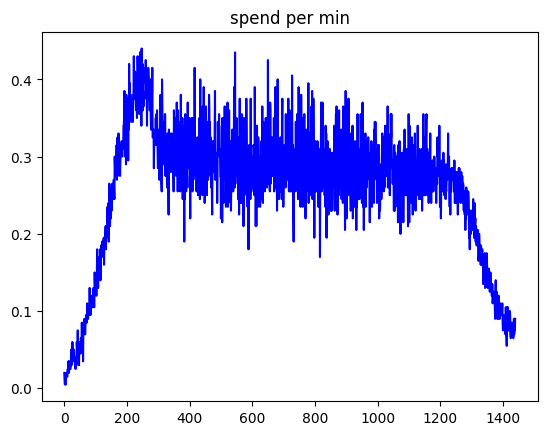

If we run a basic pacing algorithm attempting to spend the budget “evenly” through the day, delivery will look like this:

Now, if we make our pacing algorithm traffic aware, delivering according to the remaining budget and our traffic prediction, we will be able to stabilize lambda, resulting in a more optimal delivery:

In order to better visualize the impact of better pacing, let’s compare both algorithms visually and analytically.

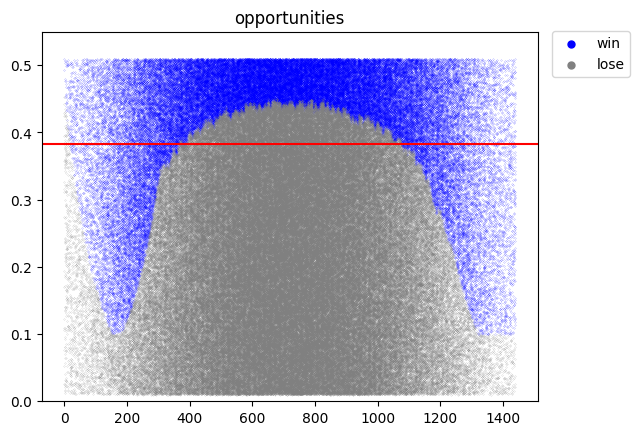

Visual Comparison

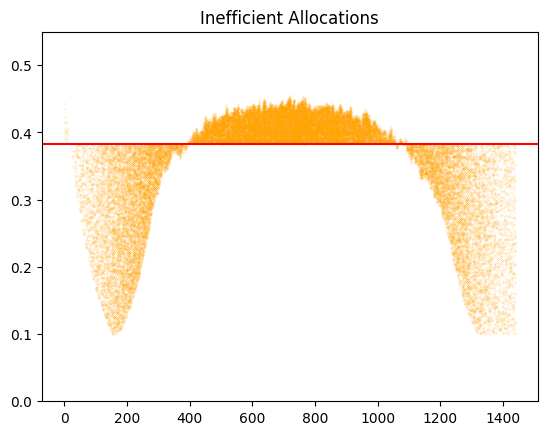

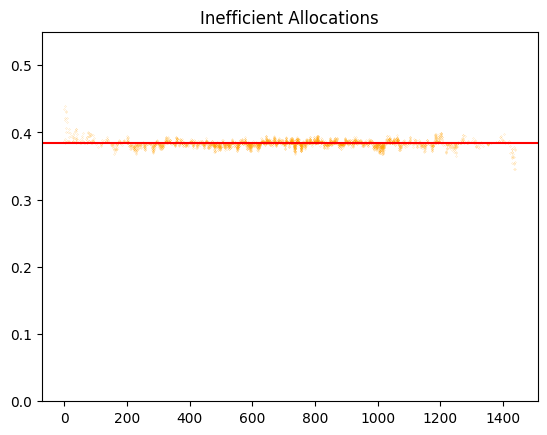

In the graph below, the red line shows the optimal delivery meaning we should ideally pick all opportunities above the line and discard every opportunity below the line.

Even Pacing

Traffic-aware Pacing

Analytical Comparison

We can use \(E(clicks) = \sum p(click)\) for opportunities selected as a proxy for the number of clicks driven by each algorithm. Dividing the number of clicks achieved from each algorithm reveals 88.2% clicks when pacing is not traffic aware.

Conclusion

Let’s review the fallacies we laid out at the beginning of this post.

The Best Ad

The goal of ads optimization is to find the best ads for every user.

The goal of ads optimization is to find the best users for every ad.

Solving with ML

We can use ML to solve the ad/user allocation.

Allocation is a constrained optimization problem and needs to be solved via auction/pacing/ML. (we will see this in more detail)

Ad Relevance

The goal of ads optimization is to build a system that maximizes ad relevance

The goal of ads optimization is to build a system that optimizes for a combination of advertiser value, revenue and user experience.

Budget Pacing

Budget Pacing is needed to spend ad’s budget smoothly

Budget Pacing is needed to maximize advertiser’s ROI (budget being spent smoothly is just a side effect).

In order to better understand this, note that probabilistic pacing spends the budget smoothly but will not actually achieve better performance (in practice it has some benefits, but those are outside the scope of this post).

Bid-shading actually improves ROI in two ways:

- Reducing bid (and price) resulting in lower costs for the advertiser and eliminating the need to manually adjust bids

- Allowing for a better allocation by lowering the bid, allowing only opportunities with a high

p(click)to win. (shown below)

Note that the lower λ becomes, the more selective we become for picking opportunities with higher p(click). This results in higher overall E(clicks) for this ad.